When Is it Selfish to Help Someone?

Is help ever selfish? More specifically, should we worry about our motivation for helping someone like a disabled child, or a older person wrestling with dementia?

Is help ever selfish? More specifically, should we worry about our motivation for helping someone like a disabled child, or a older person wrestling with dementia?

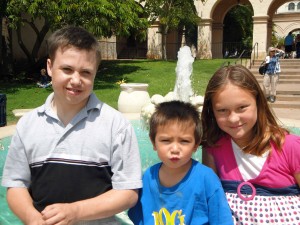

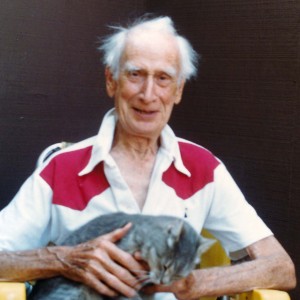

Near the middle of WATB, the action takes a detour. Until that point, the focus has been on the campaign to find out whatever has been afflicting my disabled son Joseph and to provide whatever is required to overcome it. Then, just as the family is preparing to celebrate a major breakthrough, the news arrives that my 81-year-old father is in a hospital. The immediate health crisis that put him there has already passed, but for unknown reasons he has at the same time lost his grip on reality. Feeling charged up with confidence, I respond by setting out to get him fixed up, too.

I saw parallels between the two cases. Both my son and my father lacked meaningful explanations for their problems. Most recently, I’d read in his medical record that Joseph suffered from an “encephalopathy of unknown etiology,” which is Smokescreen lingo for “something wrong with the head, danged if we know why.” When I arrived at the hospital, Dad’s doctor used similar language. The sudden onset of Dad’s confusion did not seem to support a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s. After all, a week earlier, he’d been up in a tree on his extension ladder, cutting limbs with a chain saw. So neither patient fit any obvious syndromes.

Both required a lot of care at present. Their doctors expected both to continue to require a lot of care.

Any parent wants to see his kids grow and develop new skills and eventually assume some constructive role in the world.

Any adult with aging parents wants them to retain, for as long as possible, the positive characteristics that made them so important for so many years.

If something threatens those objectives, I believe it’s a natural response to resist it. It’s common sense to want what we recognize as the best for them. So when Dad’s doctor began talking about putting him into a nursing home, I objected. We did not get along. But that was OK. I already had lots of practice with not getting along with my son’s doctors.

The remainder of that episode in the book concerns my efforts to connect with my father, in order to enlist his cooperation in coming back from the mental thicket he’d wandered into.

A friend who later read the manuscript questioned whether the story about my dad belonged in a book about a disabled child. She wrote, “there is NOTHING anyone can do for elderly people who go through what he went through, and a lot of tragedy going on in families where people believe that they can. You can love the person, and they will flash bits of themselves as they leave, but no one has ever found any way to treat it, and accepting that can make it a lot easier to deal with.”

With due respect to my wise friend, I kept it in, because my dad did recover, at least to a degree, and was able to return home for another year or two. He even flew cross-country to visit me and see his grandson one last time, and that outcome was easier to deal with than a nursing home. I saw a couple basic principles at work in my response to both situations:

- Encephalopathy, or brain injury, or dementia, or retardation, or whatever the hell you want to call it, acts like a barrier separating an otherwise intelligent individual from the rest of the world and perhaps even from himself. Piercing that barrier sounds like a worthy undertaking.

- Letting some uncaring ignoramus in a white coat dictate your course of action might be a bad idea.

But in going through the manuscript one last time before publication, I noticed something my father had said the night we finally made contact again. Perceiving with surprise how anxious I was on his behalf, he said (sighing, if I remember correctly), “I’ll try to pull things together for a little while longer.” In other words, it was going to be an effort for him. And he was going to be doing it for me.

Was I asking too much? Was I wrong?