You’re out of control

In sorting through files on my computer, I’ve come across a few paragraphs that didn’t make it into the memoir. I hate to just delete ‘em, however. They speak to the question of being in control of one’s circumstances, which has been on my mind of late.

In sorting through files on my computer, I’ve come across a few paragraphs that didn’t make it into the memoir. I hate to just delete ‘em, however. They speak to the question of being in control of one’s circumstances, which has been on my mind of late.

Eighteen months prior to the episode described below, Judy had been diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer (a challenge, I remain convinced, that came her way as a consequence of years of emotional stress and perhaps irrational guilt at having given birth to a child with developmental problems). The treatment protocol had eventually led to something called high-dose chemotherapy, a now-discontinued intervention in which the effort to kill tumor cells escalates to the point of almost killing the patient. That process complete, she’d returned home from the hospital, much weakened physically and now (at least until the residual drugs left her system) somewhat mentally unbalanced. She believed, for example, that divine intervention had cured our son Joseph of his disability. Her disappointment with me, for failing to see that, was boundless.

One Friday I took time off from my job and drove Judy back for a follow-up appointment. The oncologist thought that, in terms of the cancer, she was doing well. But her mental health troubled him, and before leaving he asked her to wait for one of his colleagues, a psychiatrist.

“Let’s go,” she said firmly to me. “I’m not sticking around here waiting for that clutz. I talked to him during the treatment. I have zero respect for the guy, and I’ve got better things to do than sit here.”

“Are you sure that’s wise?” I asked meekly. But she was already on her feet and heading for the exit, with more than her usual confidence. I followed.

Two nurses were chatting behind the front desk. We might have breezed right past them, but Judy got their attention with a nice smile and said, “I’m leaving now. Please tell the doctor I’m quite all right and I’m going home.”

Startled, the nurses looked back and forth between our faces. “Well –,” one of them began doubtfully. “But –, well, okay…” We were already out in the hallway, turning right. That was easy. At the Radiology department we turned left, passed the hospital pharmacy, then right again past the elevators. Leaving this place behind. A crowd of young medical students milled noisily outside the auditorium. Kids. New fodder for the healthcare system. There’d been a time when I’d thought I was destined to be one of them. It no longer hurt so much to know that I wasn’t.

Then we were outside, gratefully inhaling the fresh June air. Our thoughts were already on the remainder of the day. I would drive Judy home and return to my office for a few hours. The weekend was almost upon us.

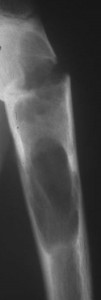

The following sequence was not pleasant. Summoned no doubt by the psychiatrist, a security guard appeared out of nowhere and promptly seized Judy by the upper arm—at the very point, in fact, where her humerus had been eroded by the largest of many tumors throughout her skeletal system.

She shrieked with pain and collapsed onto the pavement. The guard seemed taken aback: Was this merely hysterics? The way she’d begun writhing at his feet must have seemed genuine.

“She’s got a tumor in her arm,” I informed him, crouching beside her. He began to look a little concerned. On the other hand, he’d succeeded in preventing her departure. That had been his task.

The shrink arrived on the scene and took over. By this point, Judy had no further will to resist. She allowed the doctor to put her into a wheelchair and take her back inside, with assurances that they’d x-ray the arm. From there, she boarded an ambulance for a weekend of observation at a locked mental health facility.

When she returned home again, her delusions had begun subsiding—but she continued to dwell on the experience of being seized by that guard.

“Every time I think about that, my arm starts hurting again!” she cried.

“Then don’t think about it.”

“Easy for you to say!”

There are various control issues here, I guess.

Specifically not thinking about something can be a challenge for anyone.

Not having the power to correct a very bad situation is much worse. The years we spent working on Joseph’s behalf tested the limits of what could be changed. I’ve always been glad that at least we were free to try, despite resistance from certain doctors and other authority figures. Succeeding in those efforts and actually improving his life, to the extent that we did, was wonderful. We certainly didn’t succeed completely, but having tried remains a comfort.

But worst of all, I think, is the powerlessness that comes when other people take away your freedom to do as you wish. Locking Judy up seemed a little excessive. Yes, for a while there she was hard to live with, but she wasn’t a threat to herself or anyone else. I certainly hadn’t asked for that to be done.

Americans grow up hearing so much about freedom that we may take the word and the concept for granted. These days in particular, maybe we shouldn’t.