What’s Missing?

This morning, while cooling my heels in the waiting area of a medical clinic, I happened to find an article by Atul Gawande that appeared in an old issue of the New Yorker. If you’ve read WATB, you may remember that I quote him in the final pages. He’s a surgeon who appears to have an enlightened view* of how health care ought to be delivered.

This morning, while cooling my heels in the waiting area of a medical clinic, I happened to find an article by Atul Gawande that appeared in an old issue of the New Yorker. If you’ve read WATB, you may remember that I quote him in the final pages. He’s a surgeon who appears to have an enlightened view* of how health care ought to be delivered.

This article mentions a patient with terrible migraines—”She took her medicine, but it wasn’t working. When the headaches got bad, she’d go to the emergency room or to urgent care. The doctors would do CT and MRI scans, satisfy themselves that she didn’t have a brain tumor or an aneurysm, give her a narcotic injection to stop the headache temporarily, maybe renew her imipramine prescription, and send her home, only to have her return a couple of weeks later … She wasn’t getting what she needed.”)

Sometimes when we seek medical help, we get exactly what we hoped for. That was the case today. My wife was experiencing problems with her vision, and the doctor not only knew what was going on (she had a torn retina) but was prepared to address it right there on the spot. She wouldn’t say that she’s all better now, but we’re glad she got the intervention.

After such a visit I tend to feel a sense of gratitude that may be out of proportion to the help rendered. There’ve been times when the warmth of my feelings toward a helpful physician has gone right off the charts.

That’s partly because there have been other times when our experience has more closely resembled the story of the woman with migraines. WATB recounts the misadventure of repeatedly seeking professional help for a child who obviously needed help very badly, and being told repeatedly to stop worrying so much and just get on with our own lives.

Physicians who dish out that kind of treatment always seem surprised to discover that patients (or parents of patients) who are sufficiently anxious about the condition they’re facing are going to do something. We might not make choices that are advisable, but we’re determined to tackle the problem, with their support or without.

But what if nothing can be done? In the case of our son Joseph, my family did not accept that view, because his doctors gave little or no indication of having exerted themselves on his behalf. Somehow, even without a diagnosis for him, even though they would not say what was interfering with his development and causing him so much distress, they expected us to believe that there were no answers.

We didn’t believe them. And when we then took an approach that they didn’t like—he began to improve. Thereafter, we believed them even less.

Gawande’s article is about the kind of treatment that should be given to doctors’ “most difficult patients”—the ones who (like my family, until we became alienated) continue coming back with the same unresolved problem. He finds that these patients desperately need (and benefit from) someone who is willing to tackle it in a systematic way. The person offering this kind of help needs to be someone they can trust, because he will likely get somewhat involved in their lives. Obviously, this kind of high-touch care is far outside the accepted job description of your average doctor. Gawande calls it “the kind of primary-care service everyone should have,” but says it’s absolutely essential for those presenting complex challenges, as Joseph did. (He sees reason to believe that this approach would also lower costs.)

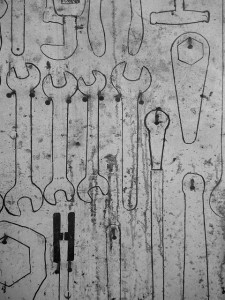

Unfortunately, the delivery of health care as we know it has no room for patients like this. We’re offered impersonal office visits and E.R. visits/hospitalizations but little or nothing in between. Gawande compares this to “arriving at a major construction project with nothing but a screwdriver and a crane.”

The news these days is all about something being called healthcare “reform,” and mounting evidence that the changes being implemented will make the missing ingredient still harder to find. I’m afraid we have gotten off course. Rather badly.

*Specifically, what I love about Gawande’s philosophy is his agreement that patients are correct in expecting their doctor to make a special effort on their behalf, and his advice to doctors to “always look for what more you could do.”