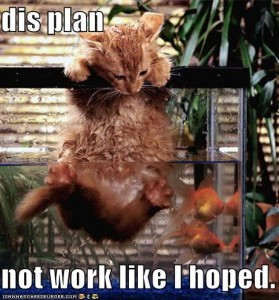

What’s the plan?

A great many years ago, I attended several lectures given by Glenn Doman and his associates, which were meant to provide direction and encouragement to anxious parents of disabled children.

One of Doman’s seemingly profound statements back then (duly recorded in my memoir) was that it’s better to plan to succeed, and then maybe fail, than it is to plan to fail and succeed at that.

Success meant getting your profoundly disabled child to the point of graduating from high school and then going off to college or to whatever lofty goal seemed most attractive.

Failure, on the other hand, was a life surrendered to the disability, possibly spent warehoused in an institution, with no attempt at exploring one’s potential. Doman had utter contempt for any parents who were willing to accept that kind of outcome for their kid. Sure, it might be easier for the family in the short run, but it was a betrayal of the relationship.

The deciding factor between success and failure—at least one of the deciding factors—was possession of a plan. Let’s assume that the goal is within the realm of possibility and that the plan for achieving it is adequate (potentially huge assumptions, I agree, but sometimes you don’t know till you try). You’ve got to have a goal and a plan. Otherwise, there’s no telling where you’ll end up.

Which sounds like the advice we get from all sides: from educators, career coaches, financial planners. Some of us may have heard it so often that the middling results we generally achieve make us feel downright inadequate.

The trouble is that most of us do have goals and plans. And to us they appear reasonable, or at least (as in the case of families who went to Doman for guidance) realizable if combined with enormous sustained effort and sacrifice.

So why, if we at least sort of know what we’re doing, is our world in such a godawful stinking mess?

I’ve been giving this question lots of thought in recent months. I haven’t posted much here during this time. An unexpected crisis has diverted a significant amount of energy into figuring out what the next phase of my career will be. But perhaps that crisis can add some depth to this speculation.

Because things are a mess not only for people growing up with poorly understood developmental disabilities (including, alas, even those touched by Doman’s methodologies). The mess extends, for example, into the corporate world, alongside of which a healthy industry has grown up to ease the transition of a great many highly experienced, loyal, long-time employees, like yours truly, displaced from their jobs by newbies and temp workers “to keep the shareholders happy.” That industry has little to say about the reality that one’s next opportunity could well be a low-paying contract position with no benefits (which, who knows, may exist at the expense of still other laid-off long-timers). (I’m striving not to descend into a rant here, although it may be too late.)

This is the new normal, my transition guides say: In the current scramble for short-term advantage, concepts like loyalty have become applicable “only for family, friends, and pets.”

And maybe not always for them, either. The other day I learned of people in the so-called millennial generation who are in favor of removing the phrase “so long as you both shall live” from the wedding vows and are further saying that marriages should be beta-tested in advance of any real commitment.

Beta-testing a marriage would accomplish the opposite of what is intended. The people involved would be practicing divorce.

So—how does one make a plan, how does one find meaningful direction in this climate? I see no realistic path forward for a life in which relationships of any kind are driven by one party’s expectation of benefit regardless of whether the other party is hurt.

Remember, I embraced Doman’s thinking (still see value in it), so when I err it’s on the side of too much commitment.

I understand that the argument could be made that I erred, or went too far, in trying to give my son options in life.

Even so, am I making too bold a claim in insisting that maintenance of our culture, or even our civilization, depends on having goals that respect the interests of all parties?

Am I making sense here? Of course, the relationship between employers and workers is not the same as that between spouses or between parents and children. But I fear all relationships are endangered, and becoming more so.

Because of poorly chosen goals, and unwise plans.