Nobody Is Safe

Many years ago, a young mother tried to make sense of the observation that my wife and I had a baby with major developmental problems. Surely, she insisted, Judy must have smoked or used drugs while pregnant—or at least we’d done something to merit that outcome. What was it?

Many years ago, a young mother tried to make sense of the observation that my wife and I had a baby with major developmental problems. Surely, she insisted, Judy must have smoked or used drugs while pregnant—or at least we’d done something to merit that outcome. What was it?

It seemed important to her for that to be true. I think her reasoning was that an absence of explanations would mean nobody was safe. Calamity could then strike her own family as easily as mine.

It’s natural for people to believe they have a handle on things. And, you know, often it seems we do. We have been taught that the world operates on cause and effect. We see that borne out every day. So given an effect, there must be a cause.

Judy and I did more than our own share of looking back for possible causes. In subsequent years I chased the question further.

My son Joseph is now an adult, still profoundly disabled, and I’ve made no progress toward an understanding of why. I do still maintain that an explanation must exist, but at this point that’s just an article of faith.

By the same token, careful action generates desired effects.

A related belief was that, faced with Joseph’s very significant problems, I as his father needed to find a way of helping him, not just enduring and coping with his situation, you understand, but improving it—if possible even completely overcoming it. I accepted that as the life work I was given to do. It would be do-able if indeed my choices and actions had the potential of producing certain outcomes.

It wasn’t the life work I had planned on. When asked about myself, even today I first claim to be a writer. But fatherhood is the role most central to my self-concept. That’s one explanation for the extraordinary lengths to which Judy and I went in trying to give Joseph more options in life.

Throughout his early years we did what we felt had to be done. It wasn’t enough. At the time, a lot of onlookers seemed to think it was a noble cause, a heroic uphill battle, and one bound to have a stirring conclusion. Because dedication and self-sacrifice are supposed to lead to that. In the meaningful universe we’re presumed to inhabit.

The theory is that we are made safe (or safer) by human effort.

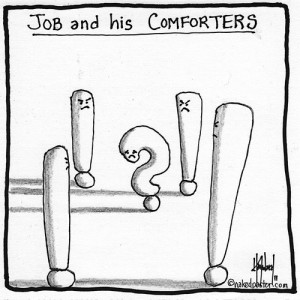

While engaged in that battle, I had to confront another disconnect between reality and expectations: In our society at least, families in difficult situations are supposed to have access to helpful resources—doctors, for example, and the whole network of related providers and enablers. But the experts we consulted were neither able to help nor even very interested in trying. Clearly, they saw my goal for Joseph as foolish, but they made no effort to show me why that was the case. Maybe they believed the facts were self-evident.

Some readers of my memoir have expressed doubt that I told the truth about those interactions. I understand. It’s easier to defend our convictions, when presented with evidence that they may not be so well-founded, than it is to confront the alternative: If the system cannot be relied upon to make a difference for people who’ve been given more than they can handle, then nobody is safe.

We, at least, were far from safe. The next challenge to come our way was a diagnosis of metastatic cancer for Judy. I recall hearing some murmurs at that point from people who had previously admired our determination to make things right. Cancer for the mother, on top of disability for the child, was simply too much to ascribe to chance. We had to be guilty of doing something wrong.

Again, one might look for causes. Maybe there was an explanation to be found in choices made along the way; maybe it was genes. Who knows! Guilty or not, we had no defense against the facts that it happened, and Judy suffered intensely, and Joseph lost his mother when he was nine years old. (No one has ever suggested any of this was his fault.)

More than two decades have passed since then. I continued as Joseph’s father/advocate, and with help I constructed a new family situation for both of us. I discovered the joys of raising a pair of kiddos who present unusual challenges only infrequently, if ever—good fortune that I’ve not taken for granted. Good fortune or evidence that, yes, sometimes choices and effort can bring about desired results after all.

But Joseph’s developmental difficulties never abated. Looking ahead to the time when I would no longer be available for him, I reflected that, if this were the life work I’d been given, a little more success with it sure would have been nice.

And now calamity has struck yet again. This time Joseph has cancer, melanoma to be specific. It was already in his lymph system before anyone knew, and it has gained a still greater foothold during a leisurely series of consultations, biopsies, scans, handoffs from one physician to another, and efforts to determine insurance coverage (insurance being much more problematic these days than at any other time in my life). In that process, I have again proved to be incapable of altering the course of events. I try to keep Joseph comfortable. I give him pain medication. When he’s anxious I try to calm him.

In his case, what I can do has never been enough—not even close to enough. Nevertheless, time and time again, like a child testing the limits of what he can get away with, I have stubbornly tried to do more for him. Because of my convictions, my programming, my inability to admit defeat.

As I sat here writing this, I began wondering how much life would be different if we lived under some kind of curse—if a vengeful deity were consciously extracting the maximum amount of sorrow, granting only enough encouragement to ensure we continued wandering about in the maze. I don’t believe that, but such thoughts do suggest themselves. At this moment, unbidden, my very affectionate nine-year-old has come along and flopped into my lap for a snuggle. Earlier this year, he too had a brush with mortality (a close encounter between a moving car and his bike). I’ve not forgotten my gratitude that he survived.

As I sat here writing this, I began wondering how much life would be different if we lived under some kind of curse—if a vengeful deity were consciously extracting the maximum amount of sorrow, granting only enough encouragement to ensure we continued wandering about in the maze. I don’t believe that, but such thoughts do suggest themselves. At this moment, unbidden, my very affectionate nine-year-old has come along and flopped into my lap for a snuggle. Earlier this year, he too had a brush with mortality (a close encounter between a moving car and his bike). I’ve not forgotten my gratitude that he survived.

I am deep in the maze, but take comfort where it can be found.