Parenting is a gamble

A journalist recently interviewed random local teenagers to learn a little about their lives and ambitions. The result doesn’t contain any particular surprises. Regarding the future, one gal hasn’t decided yet whether she’ll be a surgeon or a photographer for National Geographic. Another expects to play pro soccer. I like the outlier who acknowledges a possible destiny in which she’ll live “in a super crappy neighborhood and work somewhere like Target.” Regarding current reality and the usual land mines threatening their age group, one smiles and says, “We have the tendency to make bad decisions.” The article goes into some detail on those decisions if you’re curious.

None of that is surprising, as I said. But being the father of a teenager, I ended up checking this against the daughter’s perspective. I mean, HER buddies aren’t dropping acid at school, are they? She pointed out that things are probably a wee bit different for the neighborhood we inhabit and the school she attends.

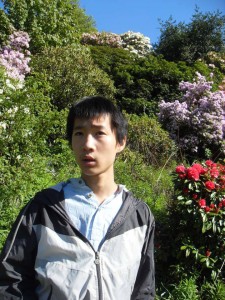

Let’s hope so. Song Yi’s insistence on moving to this suburb a decade ago was based on the ambition of benefiting from a high-end school district and association with children of overachievers, presumably to compensate for the fact that our own achievements are modest. In other words, it was an investment in the kids. I’ve written about that previously (for the same newspaper).

I do think that, thus far, our daughter has been at least partially sheltered from the worst hazards. Our little guy appears to be in a very good place as well.

So, on days when life feels a bit overwhelming, when all I see is a series of hoops to jump through, offering no reward beyond simple maintenance, I remember to be grateful. The kids are doing well, the younger two at least. That means so much to me. I’ll write more about Joseph next time.

It’s all about the kids now. For most of us, there comes a point in life when more personal longings begin to lose urgency. Instead, we think increasingly about the next generation. I see this occurring in my friends as well as myself, and realize I’ve seen it in older people all the way back.

This is the point at which any value in our accumulation of experiences and life lessons lies in whether it can empower young folks. Sure, given more bandwidth I’d still gladly apply resources to doing something for myself. However, in weighing the potential effects on my own life versus younger lives, the younger lives win out every time.

You might say I’m neglecting my own prospects in order to boost those of the next generation. Even my daughter would call that sad. A friend close enough to speak frankly might call it a denial of the reality of my own needs in favor of a gamble. To that I would say this is my conception of parenting. It is a gamble, every step of the way.

By definition, then, the outcome is uncertain. Peace of mind requires flexibility, sometimes a huge amount of it. Never mind lofty goals like becoming a surgeon, sometimes it’s too much to ask even to be able to have a conversation with your kid, or see him. For me, peace of mind comes in doing what I can.

I hope it’s understood that the goal is not to raise little hothouse orchids. They’re going to have to find their way in the real world. Even in best-case scenarios, assuming I jump through every parenting hoop flawlessly and they dodge all known land mines, they’ll encounter unforeseen trouble soon enough.

But I recall something my dad used to say, when I was little: If I don’t spoil him, who will? The process of getting young people ready for what lies ahead amounts to a nice, long metaphorical hug, maintained for as long as you decently can.