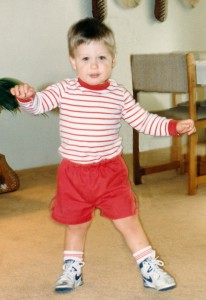

In part, WATB concerns the experience of begging our son’s doctors for help with a major problem, discovering that those experts had no idea of how to treat the problem or even much curiosity about it, and then looking elsewhere for answers.

The book includes a scene in which a newspaper reporter is interviewing me about the unconventional treatment my wife and I selected. He has already checked with a local pediatric neurologist, who informed him that we are wasting our time. Therefore, his line of questioning is confrontational. Why do we insist on ignoring professional advice? I point out that the professional advice had been to do nothing and accept our son’s undiagnosed condition as a fact of life, whereas the alternative approach we have taken is already bringing about wonderful improvements in his abilities. This claim means nothing to the journalist. Who am I, a nonprofessional, to say that my son is better or that it is due to this crackpot intervention?

Afterwards, Judy and I felt foolish for having let the guy draw us into an argument. We didn’t need to defend our choice. We only needed help for our son. At that point, anyone claiming superiority to the resource we were using would have to show us something better than mere credentials.

Still, over time we had more discussions like that, with nurses, relatives, even casual acquaintances. Their challenges had the effect of backing us into a corner. Nobody was going to make us give up this program! Even when the passage of time did not offer much assurance that the program would accomplish everything we’d hoped for.

When we did reluctantly give it up, we continued to believe another unconventional solution would pick up where the first had left off. We would discover what to do via the same determination and common sense that had gotten us to that point. We did occasionally check in with mainstream doctors, but our alienation from them was almost complete.

A better outcome should have been possible. The following thoughts are addressed primarily to professionals. I hope there is someone out there in a position to learn from our story and from this list of conclusions:

Healthcare is a partnership.

Much is written about the necessity for patients to communicate with their doctors, but in my family’s experience, it was the docs who went silent. In doing so, they didn’t advance the partnership. Instead, they removed themselves from it.

Where WERE you guys? Maybe our expectations were not entirely realistic, but we were correct in looking for more support and guidance than you offered.

I think you had other priorities. Maybe you couldn’t spend the time necessary to understand our son because you needed to clear out that waiting room. Yes, you ordered some tests; the results were either negative or inconclusive. Did the absence of a diagnosis and treatment protocol excuse you from thinking about the case more creatively? Sometimes you claimed to be hopeful that things might spontaneously improve. Maybe each of you really hoped we would continue taking our problem to somebody else. All the explanations I can think of amount to lame excuses.

It’s not about your career or professional reputation.

We all have a tendency to take ourselves too seriously. I think what we do is more important than who we are. Doctors, if helping your patients is not the first priority, I would appreciate a little enlightenment on what ranks higher.

When we were looking desperately for a way to help our son, one pediatrician mentioned cryptically that “there are programs out there for children like yours, but I’m not going to say anything about them.” Presumably, she feared censure for pointing us toward an intervention that was not endorsed by her peers. Somewhat later, when he first heard our description of what we were doing for our son, the family GP said he knew nothing about it but concluded, “If it’s working, go for it!” Later, notified that our program was frowned upon by the American Academy of Pediatrics, he changed his tune. But he never gave it any serious thought, never saw the need to learn enough to take a real stand, even though our son was his patient.

Don’t overestimate your own level of smarts.

One of the first potential treatments we learned about on our own was a medication called Piracetam, which reputedly enhanced the supply of oxygen to neural cells and possibly supported language acquisition. It was not available from pharmacies here in San Diego but could be bought over the counter in Mexico, which wasn’t far away. We mentioned it to our son’s neurologist, thinking he’d be up to speed on the subject. “Never heard of the stuff,” he said proudly. End of subject. Clearly, anything he’d not heard of was not worth hearing about. This despite the fact that Piracetam had been the subject of a recent study at the local children’s hospital. We’d already read the study. My wife had phoned one of the researchers involved.

The doctor’s confidence that he knew everything worth knowing would have impressed us more if he was offering a reasonable alternative. So do you think we visited a Mexican farmacía and began medicating Joseph ourselves? You’d better.

Bad-mouthing your competition is unbecoming.

I’ve found this habit particularly noticeable among altie providers, those selling off-label hyperbaric oxygen, auditory therapy, fetal cell therapy, etc. When we browsed among them, we repeatedly found practitioners haunted by jealousy of competing clinics. They spoke resentfully of people who had stolen their ideas or who made claims that only they themselves had the right to make. They gave the impression of not having the resolution of our son’s problems as a high priority.

All these errors on the part of healthcare professionals have the effect of making patients feel very much alone. In a sense, feeling alone is getting a glimpse into reality. Help from one human to another can go only so far. But I think patients have the right to expect a good college try at providing that help first.

Now as the patient, or rather the father of the patient, I too screwed up. Deprived of the benefit of your expertise, I had to rely only on my own reasoning and my own sense of what felt right. But my mistakes were the result of ignorance. Yours amount to abdication.

The host of this show, which is nominally for an older audience, asked for thoughts that might be useful to grandparents of a disabled child. My basic response to that was:

The host of this show, which is nominally for an older audience, asked for thoughts that might be useful to grandparents of a disabled child. My basic response to that was:

Although I’d much prefer not to single out anyone’s writing in this way, the following bit of promotional copy for a self-published novel illustrates a problem that’s doing a lot of damage. I found this on a nicely printed postcard next to a display copy of the book in question, and the first paragraph grabbed my attention. Apparently, the book it describes is a somewhat cerebral thriller tied in with recent history. Reading it, I felt a tug of interest. This book might be good!

Although I’d much prefer not to single out anyone’s writing in this way, the following bit of promotional copy for a self-published novel illustrates a problem that’s doing a lot of damage. I found this on a nicely printed postcard next to a display copy of the book in question, and the first paragraph grabbed my attention. Apparently, the book it describes is a somewhat cerebral thriller tied in with recent history. Reading it, I felt a tug of interest. This book might be good! One day last week I got a call from one of the ladies running

One day last week I got a call from one of the ladies running