Interview on Family Focus Radio

Click here to listen to a nice 30-minute interview with host Line Brunet. Excerpt below:

Click here to listen to a nice 30-minute interview with host Line Brunet. Excerpt below:

Click here to listen to a nice 30-minute interview with host Line Brunet. Excerpt below:

Click here to listen to a nice 30-minute interview with host Line Brunet. Excerpt below:

Dave and Bill at Cyberhood Watch Radio gave me my first one-hour interview, and the time flew past. Click here to listen. Excerpt below:

Dave and Bill at Cyberhood Watch Radio gave me my first one-hour interview, and the time flew past. Click here to listen. Excerpt below:

It was a pleasant surprise to learn that What About the Boy? was one of a handful of new books mentioned on TV Saturday. Click here to see the video clip.

A friend asked what I did to achieve such notice, but this one was an unexpected gift from the blue. On the other hand, some work has gone into lining up a series of media interviews. When possible, I will begin posting links to those discussions as they occur. The first is scheduled for 8:35 p.m. Eastern Time on Monday.

UPDATE: That first interview (via Skype) is now available here. Select the file dated 08-08-11. My segment begins at about the 35-minute mark.

INTERVIEW EXCERPT: “… I’m proud of what we did. But you know I really can’t imagine any other course of action. It was just a thing that had to be done. Now, not everybody reacts as we did. Not everybody has exactly the same variables in their life. If that happened to me now, if I had a child at this point who had that kind of problem, I’m not sure I would have the energy to do it. But I’m so glad that we did it. And even the things that we tried that did not work out—. Could you go on with your life knowing that there was an option that you didn’t try? For me, the answer was no. I had to try.”

Heard an anecdote today. It may be apocryphal but whether it actually happened really doesn’t matter.

Heard an anecdote today. It may be apocryphal but whether it actually happened really doesn’t matter.

A little old lady is in bed late at night, with the lights out, and she hears somebody trying to break into her house. She dials 9-1-1 but (due to budget cuts–entirely plausible here in California) gets only voicemail. She knows she can’t wait, so she hangs up and checks the phonebook for a doughnut shop. Calls that number and asks the manager if any policemen happen to be there. He says, “Well, yes, as a matter of fact we have two sitting here right now. Would you like to speak to one?” Next thing she knows, the bad guy is getting hauled away in handcuffs.

What’s the point of that tale? Quite simple: If there’s something you absolutely must have, or something your kid needs (which is the same thing), and the normal channels for accessing help aren’t working for you, don’t be surprised. Do be prepared to think creatively.

Maybe it’s a reflection on the quality of my own creative thinking, but I usually find that the first clever idea doesn’t work out that neatly. Staying with the above analogy, the shop is closed, or the cops have already come and gone, or maybe I can’t even find the blasted phonebook. In that case, there needs to be a Plan C. Any number of wild ideas will beat the alternative of giving up. What’s got you stumped right now? And how are you going to get around it?

If you haven’t seen it yet, a community newspaper serving Del Mar, California and the surrounding area ran a pretty decent article on the book last week. To read it, please click here.

If you haven’t seen it yet, a community newspaper serving Del Mar, California and the surrounding area ran a pretty decent article on the book last week. To read it, please click here.

Is help ever selfish? More specifically, should we worry about our motivation for helping someone like a disabled child, or a older person wrestling with dementia?

Is help ever selfish? More specifically, should we worry about our motivation for helping someone like a disabled child, or a older person wrestling with dementia?

Near the middle of WATB, the action takes a detour. Until that point, the focus has been on the campaign to find out whatever has been afflicting my disabled son Joseph and to provide whatever is required to overcome it. Then, just as the family is preparing to celebrate a major breakthrough, the news arrives that my 81-year-old father is in a hospital. The immediate health crisis that put him there has already passed, but for unknown reasons he has at the same time lost his grip on reality. Feeling charged up with confidence, I respond by setting out to get him fixed up, too.

I saw parallels between the two cases. Both my son and my father lacked meaningful explanations for their problems. Most recently, I’d read in his medical record that Joseph suffered from an “encephalopathy of unknown etiology,” which is Smokescreen lingo for “something wrong with the head, danged if we know why.” When I arrived at the hospital, Dad’s doctor used similar language. The sudden onset of Dad’s confusion did not seem to support a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s. After all, a week earlier, he’d been up in a tree on his extension ladder, cutting limbs with a chain saw. So neither patient fit any obvious syndromes.

Both required a lot of care at present. Their doctors expected both to continue to require a lot of care.

Any parent wants to see his kids grow and develop new skills and eventually assume some constructive role in the world.

Any adult with aging parents wants them to retain, for as long as possible, the positive characteristics that made them so important for so many years.

If something threatens those objectives, I believe it’s a natural response to resist it. It’s common sense to want what we recognize as the best for them. So when Dad’s doctor began talking about putting him into a nursing home, I objected. We did not get along. But that was OK. I already had lots of practice with not getting along with my son’s doctors.

The remainder of that episode in the book concerns my efforts to connect with my father, in order to enlist his cooperation in coming back from the mental thicket he’d wandered into.

A friend who later read the manuscript questioned whether the story about my dad belonged in a book about a disabled child. She wrote, “there is NOTHING anyone can do for elderly people who go through what he went through, and a lot of tragedy going on in families where people believe that they can. You can love the person, and they will flash bits of themselves as they leave, but no one has ever found any way to treat it, and accepting that can make it a lot easier to deal with.”

With due respect to my wise friend, I kept it in, because my dad did recover, at least to a degree, and was able to return home for another year or two. He even flew cross-country to visit me and see his grandson one last time, and that outcome was easier to deal with than a nursing home. I saw a couple basic principles at work in my response to both situations:

But in going through the manuscript one last time before publication, I noticed something my father had said the night we finally made contact again. Perceiving with surprise how anxious I was on his behalf, he said (sighing, if I remember correctly), “I’ll try to pull things together for a little while longer.” In other words, it was going to be an effort for him. And he was going to be doing it for me.

Was I asking too much? Was I wrong?

Do you ever look back at an apparently random occurrence and marvel at the chain of events it set in motion?

Joseph, the boy in What About the Boy, came into this world, at least in part, because of a stranger’s child.

Judy and I were strolling through the park one pretty Sunday afternoon, way back in 1984, and I just happened to notice a little girl in a bright sunsuit, toddling in the grass around a blanket upon which her parents lazed.

Gee, I thought. That looks nice. Hmmmm.

Until then, neither of us had seriously entertained the notion of having kids. We were in our thirties, but I don’t know—we probably felt that we were still not too far removed from being kids ourselves. We’d stayed preoccupied with careers and deciding where we wanted to live. So a few minutes later, as we sat on a low stone wall beside the bay, Judy couldn’t believe it when I tossed out the suggestion that we make someone new.

“Really? Are you sure that’s what you want?” She looked almost frightened. Oh, she warmed to the idea quickly enough, but while wrestling with it in those first few moments, she blurted a warning that turned out to be prophetic. “If we ever split up,” she said, “this will be your kid.”

We never talked about splitting up. I don’t know why she said that, other than as a test of my commitment.

Turns out we both had plenty of commitment.

* * *

Skipping ahead a few years, another stranger’s youngster crossed our path and set a new chain of events into motion. This time, Judy was standing at a counter at Joseph’s doctor’s office, writing a check, when a child rolled onto her foot. Looking down, she recognized disability in an Asian skin. As Joseph had been until recently, this kid was saddled with a problem that prevented him from crawling or doing much of anything.

A conversation ensued with the mother, who was an immigrant from Taiwan. When they learned that we’d helped our son overcome a problem similar to the one they faced, both parents wanted to meet us. Before long, we were very close, and when they returned to Taiwan, they wanted us to visit them there. Until then, neither of us had entertained the idea of traveling to Asia at all. We knew virtually nothing about that side of the world.

Well, we went. And I absolutely loved Taiwan, and everything I could see about Chinese culture, but let’s save that story for another day.

* * *

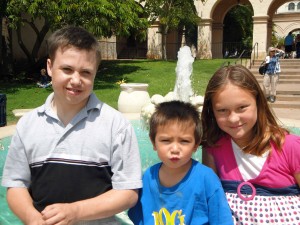

All human relationships end sooner or later, and one day Judy and I did split up. Cancer took her. Let’s save that for another day, too. (All this is in the book, by the way.) But because the little girl in the park prompted a decision to have a child of our own, and because in turn our boy broadened our horizons sufficiently, one day I found myself traveling solo in mainland China, relying on a recently acquired and very imperfect command of Mandarin. That’s where I met Song Yi, who later became Joseph’s stepmother, and who then blessed Joseph with two charming siblings.

Nobody could have planned out a story like this. And I’ll bet you’re thinking of similar astonishing chains of events. Want to share?

When I took a personal writing course from Tom Larson a few years ago, I learned that memoir focuses on a single phase of the author’s life (as opposed to, say, autobiography, which starts with the author’s birth and hits all the highlights from there on). Memoir, as it’s conceived these days (or as Tom presented it anyway, and he should know), involves reflection about how just one piece of life has changed the writer.

Reflection and change are the key words.

Memoirists examine their selected piece of life and in the process come to conclusions about the significance of past relationships, or trials they’ve faced, or the effect on them of involvement with certain ideas.

The earliest memoirs I recall reading were not like this. They gave the inside scoop on important, well-known events from the point of view of the principal actors. Examples are The Double Helix, by James Watson, and One Life, by Christiaan Bernard. (Hm, this kind of fare suggests that I must’ve had a fascination with medical science long before the events in my own story.)

Some memoirs today have the same rationale (Let’s Roll!, by Lisa Beamer comes to mind). But the recent excitement about the genre concerns something different. Nowadays we have “literary memoirs,” in which mostly unknown people, who have no connection with ground-breaking discoveries or newsworthy events, explore their specific situations in a way that sheds light on a more universal story. In these books, the subject tends to be an intense emotional—perhaps a very personal—experience. Because of that, even though the writer may have emerged from the experience by the time he begins setting it down on paper, the result is not the sort of thing he can plan out in advance, because the process of working through all the emotions involved can lead to unexpected conclusions.

There is conflict between what I the writer knew then, when I was doing it, vs what I know now. Apparently, it’s not at all unusual for the memoirist looking back to perceive that what he once took for truth was a pack of lies.

That’s the story behind What About the Boy?. My memoir began as little more than private journaling–just recording the facts as they occurred. At that stage, I gave little or no thought to publication. The writing was just an emotional outlet. Later, I thought I might have the makings of a kind of how-to book. This is how we rescued our kid. If your kid has problems, you can do it, too. Well, that idea came and went, but as I dealt with the tail-end of that idea, I realized that what I really had was an emotional journey that ultimately concerned where one turns when one must go somewhere but has no reliable guidance.

Writing often veers off in an unplanned direction, doesn’t it? I sat down here today intending to discuss some of my favorite memoirs, and instead I’ve said what makes memoirs in general interesting. But I would still like to offer a few excellent examples, before becoming totally fixated on promoting my own. Here are three that fit the definition, despite being pretty far apart in subject matter. Please click the links to read the reactions I (and others) have posted on them.

What memoirs have you enjoyed?

I’m fascinated by this continuing and accelerating erosion of the control that traditional gatekeepers have held over our lives. Lots of observers, with various different axes to grind, continue to write about this.

Some note that automation, in the form of interactive websites and self-service gas stations and cash registers, is adding to unemployment. Or, at least, it’s eliminating jobs that don’t add value to what others have created.

Some point to the ways in which amateur online journalists are now providing a reality check on big media, and myriad other small operators are using technology to overtake the complacent Goliaths in our world.

This trend has casualties, but I think it’s empowering.

One example: When the time arrived for me to show What About the Boy? to the publishing realm, I found myself repeatedly bumping up against literary agents and acquisitions editors who claimed to see merit in my story but feared to get behind it. Some admitted to being unable to proceed simply because my name is not a household word. The book exists anyway because I realized I didn’t need them.

“No one is going to pick you,” Seth Godin points out. But that’s OK, since nowadays you can “pick yourself.”

In short, power is shifting from big organizations to small, informal groups and individuals.

If you are a parent with concerns about your kid, which nobody is adequately addressing, this trend is especially good.

I think the ultimate appeal of What About the Boy? is its presumption that individuals have the right, and the power, to make decisions for themselves, as opposed to letting authority figures hand them a circumscribed menu of choices.

Now, this comes with the understanding that we may not always make good choices. (By the same token, my ability to publish this book does not automatically mean I can do it well or deliver a quality product.) Eliminating gatekeepers does not guarantee success. On the other hand, how often do gatekeepers facilitate success? How often are they middle men, at best? At least, when we take responsibility, the choices and the results of those choices are ours. If we care, we will do our very best, and will enlist real help where needed. It’s true that sometimes certain desired outcomes remain out of reach. Nevertheless, choosing our own response to whatever fate sends our way makes us less a victim and more a participant in the way life unfolds.

I see people doing this daily as I monitor online discussions concerning developmental disabilities.

A lady reports that her nephew is constantly walking on his toes, and that the parents are taking him to a podiatrist. This triggers a rather well-informed discussion of what toe-walking may indicate and how others have treated the underlying cause.

One parent asks about the merits of homeopathy. Another responds, “Did absolutely nothing for us.“ The first comes back for more details. “How long did you guys try it for?”

Yet another parent complains that her child is expected to wait a full year before the neurologist can see her. I am among those who step in with suggestions, and the collected responses make fascinating reading, both about the smartest way to get in front of a good neurologist and about what to expect.

What About the Boy? describes my family’s quest for help in the days way back before the Internet was available. We took our son to a doctor who acknowledged that he had major problems, but the doctor had absolutely nothing to recommend in terms of treatment.

We insisted, “There’s got to be something we can do for him!”

“Oh, there are programs out there for children like yours,” the doctor said. “But I’m not about to suggest anything. “They’re controversial.”

“How are we supposed to make intelligent decisions if we don’t know our options?” my wife demanded.

“Talk to other parents,” was all the good doctor would suggest. And that hint started us down a very long path.

Sometimes, I think, gatekeepers don’t even want that role. I think the more intelligent ones hate to find themselves in the path of highly motivated seekers en route to an objective. They know, and we know, that if they can’t help us along the way, they’ve got no business being there.

As always, comments are welcome.