Could Anyone Have Predicted This Course of Events?

Do you ever look back at an apparently random occurrence and marvel at the chain of events it set in motion?

Joseph, the boy in What About the Boy, came into this world, at least in part, because of a stranger’s child.

Judy and I were strolling through the park one pretty Sunday afternoon, way back in 1984, and I just happened to notice a little girl in a bright sunsuit, toddling in the grass around a blanket upon which her parents lazed.

Gee, I thought. That looks nice. Hmmmm.

Until then, neither of us had seriously entertained the notion of having kids. We were in our thirties, but I don’t know—we probably felt that we were still not too far removed from being kids ourselves. We’d stayed preoccupied with careers and deciding where we wanted to live. So a few minutes later, as we sat on a low stone wall beside the bay, Judy couldn’t believe it when I tossed out the suggestion that we make someone new.

“Really? Are you sure that’s what you want?” She looked almost frightened. Oh, she warmed to the idea quickly enough, but while wrestling with it in those first few moments, she blurted a warning that turned out to be prophetic. “If we ever split up,” she said, “this will be your kid.”

We never talked about splitting up. I don’t know why she said that, other than as a test of my commitment.

Turns out we both had plenty of commitment.

* * *

Skipping ahead a few years, another stranger’s youngster crossed our path and set a new chain of events into motion. This time, Judy was standing at a counter at Joseph’s doctor’s office, writing a check, when a child rolled onto her foot. Looking down, she recognized disability in an Asian skin. As Joseph had been until recently, this kid was saddled with a problem that prevented him from crawling or doing much of anything.

A conversation ensued with the mother, who was an immigrant from Taiwan. When they learned that we’d helped our son overcome a problem similar to the one they faced, both parents wanted to meet us. Before long, we were very close, and when they returned to Taiwan, they wanted us to visit them there. Until then, neither of us had entertained the idea of traveling to Asia at all. We knew virtually nothing about that side of the world.

Well, we went. And I absolutely loved Taiwan, and everything I could see about Chinese culture, but let’s save that story for another day.

* * *

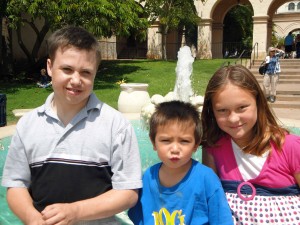

All human relationships end sooner or later, and one day Judy and I did split up. Cancer took her. Let’s save that for another day, too. (All this is in the book, by the way.) But because the little girl in the park prompted a decision to have a child of our own, and because in turn our boy broadened our horizons sufficiently, one day I found myself traveling solo in mainland China, relying on a recently acquired and very imperfect command of Mandarin. That’s where I met Song Yi, who later became Joseph’s stepmother, and who then blessed Joseph with two charming siblings.

Nobody could have planned out a story like this. And I’ll bet you’re thinking of similar astonishing chains of events. Want to share?