Clout and lack of clout

First a data point: A recent issue of The New Yorker carries a fascinating article about a family whose child has an exceedingly rare genetic disorder. It’s somewhat heart-wrenching (and familiar), as are all stories about kids with developmental problems. These stories always involve anxious parents rushing from one appointment to the next in search of answers.

“As one conjecture after another was proved wrong, the specialists lost interest; many then insisted that the cause of Bertrand’s illness lay in someone else’s area of expertise. ‘There was a lot of finger-pointing,’ Christina said. ‘It was really frustrating for us—our child hot-potatoed back and forth, nothing getting done, nothing being found out, nobody even telling us what the next step should be.'”

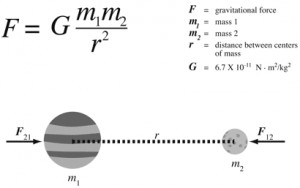

The article also is of broader public health interest, since the family’s quest eventually leads them into the painstakingly complex process of exome sequencing—a relatively new way of identifying genes that might be at the root of an individual’s unexplained condition. About two years after turning down that road, they finally got the explanation they’d sought: Their four-year-old suffered from a genetic mutation possibly shared by no one else in the world. And without more cases, “there was virtually no possibility of getting a pharmaceutical company to investigate the disorder, no chance of drug trials, no way even to persuade the FDA to allow Bertrand to try off-label drugs that might be beneficial.”

Here’s where this data point becomes enlightening for the rest of us facing uphill battles. Bear in mind that for several years now this family had been traveling extensively to put their son in front of the most prominent specialists available, in the process spending sums well beyond the reach of many ordinary middle-class families. I’m glad they could. I’m glad too that they had the fortitude to keep going past all the apparent roadblocks—and they kept going at this juncture as well. When told that more patients were needed, Matt, Bertrand’s dad, said, “All right, we’ll get more.” And they did. You see, in addition to benefiting from recent (expensive) advances in genetic sequencing, they also had Matt’s stature as a computer scientist. He wrote an essay describing the problem, posted it on his blog, and watched it go viral within half an hour. Eight days later they’d found two other families grappling with the same problem, and at least seven more showed up over the next year. Joining forces, these people formed a proactive community that has brought serious money to bear on studying their kids’ condition and has even resulted in collaboration among researchers.

Their problem is being taken seriously.

Frankly, that’s not quite the way the story unfolds for families with less clout.

This story calls to mind an older data point involving the family of Catherine Maurice (a pseudonym), who wrote a book about rescuing both of her kids from autism by hiring a specially trained full-time therapist that she flew in from the other side of the country.

And it calls to mind various personal experiences. For example, there was a period of time in the 1990s when parents everywhere (those whose kids might be on the autism spectrum) wanted access to Secretin. It was available only by prescription, and generally only as a treatment for a different medical condition, i.e., applying it to autism was definitely off-label. I was lucky enough to find a physician who would write a prescription for it. But then I couldn’t get the prescription filled. There seemed to be a sudden worldwide shortage. When I finally located a pharmacy that stocked Secretin, they wouldn’t sell it to me. Someone on their staff had an autistic kid and he already had dibs on it all. And much more recently, I’ve sought exome sequencing. Earlier posts this year show the trajectory of that effort.

So what are the rest of us to do, those of us with no unusual influence or resources?

Sure, life will always be unfair. All parents feel some degree of concern for underprivileged kids, even while striving to improve the advantages enjoyed by their own. I could go off on a tangent about the adults who do better in life when they screw up on a royal scale than do schmucks who do everything right, but I’m trying to stay in my lane.

Inequality of opportunity is hardest to abide when it affects kids already afflicted by developmental disability.

In my own family’s story, sheer determination moved us a long way down the road. For example, I did eventually get my hands on some Secretin (and established that it wasn’t the hoped-for magic bullet). But we pretty much ran out of gas a long time ago. Every now and then the motor sputters and kicks so that it seems we’re moving ahead. We may yet learn more, or even do more, to improve Joseph’s prospects in life.

But what I’ve attempted in recent years has been motivated largely by a desire to empower younger families, to warn them away from unproductive attitudes and avenues and to encourage them to hang on to the dream.

Maybe that’s too abstract to be of tangible benefit. So I would like to conclude with a nod to the work of an exceptional parent I met recently. In raising and advocating for a developmentally disabled daughter, Meena Tadimeti saw an unmet need for identifying local resources. She formed the Modesto Special Parents Network and runs a website where families can access ways of learning how to help their kids. This is precisely the kind of information my family wanted back in our early, pre-Internet days. There is strength in numbers; we grapple with a variety of disorders, but we are many. And I continue to expect the best for everyone who insists on an improved outcome.