Seeking resolution

The last several weeks have contributed a new dot in a pointillist picture that has been slowly emerging, like a photo in the developer tray, throughout my son’s life.

The last several weeks have contributed a new dot in a pointillist picture that has been slowly emerging, like a photo in the developer tray, throughout my son’s life.

The image still isn’t entirely clear. Often I have thought it shows a medical system that’s content to ignore the needs of helpless children who depend utterly on whatever interventions it might offer. That’s what I see when I’m angry. At other times, it looks more like a depiction of the futility of human effort. But the picture continues to take shape, with excruciating slowness, and maybe something more encouraging can yet emerge.

A little background: Joseph has a poorly understood developmental problem that has prevented him from being able to do anything constructive throughout his life, or even to interact normally with others. My memoir covers some of the avenues his mom and I pursued in hopes of making things better for him. And with his cooperation we did actually improve the quality of his life. Significantly. I think our story shows in part that it is worthwhile to extend yourself, and take risks, in pursuit of a cherished goal.

But our achievement of that goal was far from complete, at least partly because we never really knew what we were dealing with. Until you identify your problem, anything you do is guesswork. At various times in his early years Joseph’s doctors used terms like brain injury, cerebral palsy, encephalopathy of unknown etiology, autism, and (my favorite) “he’s got something but we don’t know what.” Treatment programs for such conditions have tended to be controversial, which means not endorsed by mainstream medicine. Which does not mean mainstream medicine had anything of substance to offer. (Please note that I do not blame doctors for what they don’t know. I do sometimes think a bit more effort on their part, in the interest of learning how to help a problem patient, would not be amiss.) For lack of an option, Judy and I took the route into controversy. Quite a few people we knew, or knew of, did likewise on behalf of their developmentally challenged kids — and claimed success! However, without a real diagnosis, we had little assurance that our efforts were being properly directed. When you do something for a period of time — something that may be very difficult and/or very expensive — and you see no result, what does that mean? Should you stop, or should you double down on the theory that more is needed? Questions like that can make a parent crazy.

When Joseph was 16 or 17 years old, a doctor visiting from the East Coast saw him and told me, categorically, that he was not autistic. Instead, various subtle cues I hadn’t even noticed meant that a genetic error was almost definitely at the root of his problem. Well, perhaps that would explain why all of the interventions reported to help with autism had failed us so miserably.

Next question: What, pray tell, is the genetic error? Maybe I’m just a geek when it comes to medical issues, and maybe I know only enough to be dangerous. But it seemed to me then, and still does more than ten years later (This spring he will have his 29th birthday; my boy is practically middle-aged!) — it seems to me that understanding the underlying mechanism would be a necessary first step toward real treatment. I mean, if for example he cannot produce some enzyme or cannot regulate some metabolic process, conceivably something might be done about that. Isn’t this worth exploring?

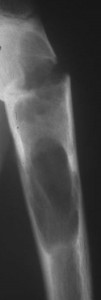

What has followed has been a series of widely-spaced visits with an eminent specialist in genetics/dysmorphology (ironically, someone who examined Joseph as a newborn and pronounced him free of genetic abnormalities, based on technology available at the time). I’ve tended to seek out meetings with this gentleman whenever my personal research suggests a known condition we might test for.

For example, in 2007 I read about Smith–Lemli–Opitz syndrome (SLOS), an inborn error of cholesterol synthesis (Joseph’s blood tests always showed low cholesterol) that shares many characteristics with autism, e.g., hypersensitive to auditory stimulation and obsessive-compulsive behaviors such as hand flicking. This sounded promising to me, but the doctor thought it highly unlikely because that syndrome comes with other traits that Joseph doesn’t exhibit. He did order a test, to placate me, but due to a series of snafus with the lab that test was never run.

Late in 2013 I read about 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, which comes with heart abnormalities, lowered communication skills, and poor ability to stay on task, and is impervious to autism interventions. Another possible match! Back Joseph and I went to the good doctor. Again, he said that was an unlikely diagnosis. He did mention this time that the state of the art has advanced significantly in diagnosing missing/duplicated genes and offered a reasonable hope that something called an array comparative genomic hybridization test might yield the answer for which I’ve searched so very long.

Incredibly, after six weeks I cannot seem to get this test performed. Repeatedly, I’ve taken Joseph to the lab for a blood draw, and the lab has said the paperwork is unclear, the order isn’t in their computer, etc. Somehow, going back to the doctor’s office does not help. Calling means leaving a voicemail that isn’t returned. Barging in there in person gets me a nice receptionist who says the doctor and his secretary are “not in today,” and who prints out more paper that the lab again refuses to accept

This test IS going to happen. I am not giving up.

But what picture is coming together with all this? Are we seeing primarily the sublime indifference of people presumably in a position to help? Is this simply an object lesson in my own unproductive, compulsive behavior? In weak moments I begin to wonder how productive any activity truly is. All this bustling about certainly keeps one occupied, but results are nice, too, aren’t they?

By the way, in warming up to get all this off my chest, I typed the following phrase in Google:

WHY IS IT SO HARD TO GET ANSWERS?

The first hit to come up with that is a post by another parent, also worried about her kid: