A glimpse through the window

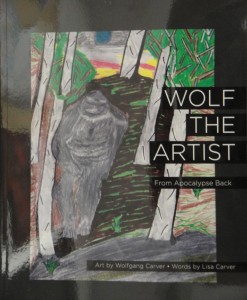

Several weeks ago, I learned about a little book that is the product of a collaboration between a developmentally disabled teenager and his mother. He contributed several arresting illustrations, and she added written context. I ordered a copy and suggest that you consider doing so as well.

This book provides touching insight into the perspective of Wolf, the young man, as interpreted by the person who comes closest to understanding him. She explains that the things we find important do not register with her son. For example, he has no interest in the authority, social status, or mood of another person, or in passing the time with “small talk.” Instead, he cares about animals, Bigfoot, ghosts, life on other planets, and meteor showers, or as he puts it, “realistic things.”

While I think anyone would welcome the opportunity to consider another perspective, this particularly fascinates me because I’ve spent so many years wondering how my own son, Joseph, sees the world. Unfortunately, in our case we don’t have the avenues of artwork or verbal language. If I know what’s going on in Joseph’s head, it’s only because of clues like his facial expression. He can convey a lot that way, but a very big gap remains for a dad who relies on words as heavily as I do. The situation feels somewhat like the one in the movie Mr. Holland’s Opus, in which the music-loving father must come to terms with the fact that his son is deaf.

For a while, Wolf was drawing disturbing images because, he said, he needed to get it out of his head. His mom connected that preoccupation with the influence of “reality bullies” who believed he needed to spend his time in school. He had concluded by that point that school was a place where “I felt sick in my body and sick in my head.” She advocated for him, as of course a parent must, and won his release. After that, “his artwork was no longer plagued by disasters.”

“The older Wolf got,” the mother tells us, “the more pressure the world put on him to normalize … and it just wasn’t happening.”

I know all too well the feeling of having something not happen. I hesitate to use the word “pressure,” because it sounds so negative. I continue to think that trying to help a child “normalize” is a fundamentally good thing. Nevertheless, in so many cases we make our best efforts (granted, with mistakes along the way). We put our trust in those whom we believe merit that trust. We couple our efforts with theirs. And, as another parent of a disabled kid puts it, that pursuit turns into “a fool’s errand.” It can make the parents crazy with frustration, let alone the child.

How do things end up going so wrong?

I do maintain that something is going wrong here. There is no question that, from any objective measure, including degree of control over his own circumstances, Joseph’s quality of life leaves a lot to be desired. And Wolf’s mom says up front that he “deals with chronic discomfort and confusion” that are due to his condition. It’s entirely reasonable for anyone to want to relieve a child of such problems. These are problems.

What are we to make of this? It’s the question I’ve had the most trouble with, over the years, and the one that other people seem to have the hardest time answering as well. All I can say is that a problem that cannot be resolved to our satisfaction is a problem we must make the best of. We must live with it, and we owe it to ourselves and to everyone around us to make life as good as it can be.

Wolf the Artist provides a fine example of a family doing just that. Please check it out.