Cutting to the chase – What’s important & where is it?

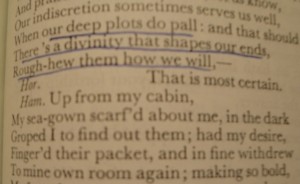

At an earlier stage in life, I underlined key passages in everything I read. Didn’t matter if it was a textbook on histology or a play by Shakespeare. I wanted to find the kernel of usable truth in there—the basic idea or fact that could make a difference in how things turned out for me.

In the case of a textbook, read in preparation for a looming exam, the rationale for this is obvious. But often I had a longer view. I assumed that most of what I read might have long-term relevance. I didn’t expect to have time to read the whole book more than once, so I wanted to leave markers to enable my future self to return and quickly find the takeaway among all those less important words.

Then, having extracted the essence from many books, presumably it would be no insurmountable task to assemble all those snippets, look for commonality or some kind of synthesis, and be able to say with some finality This much is true.

And then, of course, to be more enlightened, or more effective—more in sync with the great minds that had gone before. (The notion feels slightly sophomoric at this point.)

I’m reminded of that long-dormant impulse by the advice I hear nowadays, as a blogger, to populate my writing with keywords and bullet points. The idea is to make information easily accessible by web surfers and search engines alike.

I don’t seem to be doing a very good job of that here.

Now, in my day-job as a technical writer, I do know I’m supposed to provide just enough information for my readers to act upon. For example, someone reading the user guide for a new mobile phone has a specific purpose and doesn’t want to spend a whole lot of time accomplishing that purpose. Nobody does. They have too many other things to do.

But let’s say someone needs to get to the bottom of a controversial question, of which there are many in life. In my family’s story, when our baby had a developmental problem, we wanted answers and we wanted them yesterday. Time was passing, and the other kids were leaving him far behind. Doctors told us there was nothing anyone could do for him. But alternative provider A assured us that he could help. Alternative provider B warned us to pay no attention to A and to trust him instead.

We all want life to be simpler. We want to absorb a succinct message and have it be sufficient.

So in a situation like my family’s, eagerness to find a quick answer may drive us to uncritical acceptance of the wrong one. Human nature being what it is, deciding that one option is best can result in a rigidity that prevents us from reevaluating when new information comes along. The trouble is that the discarded choice may be less wrong than it is incomplete. In our story, the mainstream doctors had a valid point—but so did some of the alternatives. By ignoring the pediatrician’s advice, we did improve our son’s quality of life. On the other hand, we could not completely overcome his problems, and in the process of trying we damaged ourselves. The mainstream doctors had warned that we needed to look after ourselves as well as our son, and it turned out they were right about that.

It’s a challenge, distilling my experiences down to a handful of pithy truths. I hope that people can avoid some of the mistakes we made along the way, but to do so they probably need to travel some of that road with us, at least vicariously, on the page.